Measuring the universe's breathing

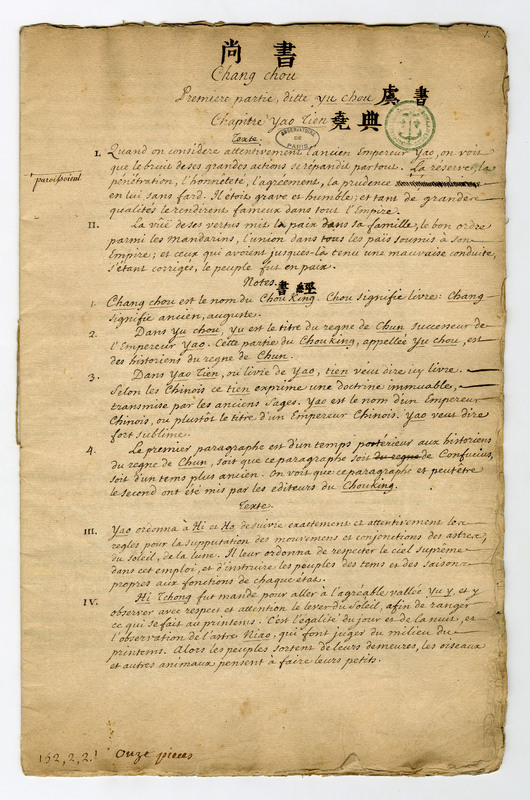

As soon as, thanks to his virtues, Yao managed to bring peace to his family and Empire, his first political act was to watch over the calendar. Hi Chou, Hi Tchong, Ho Chou and Ho Tchong (in Father Gaubil's transcription), four Mandarin astronomers, were in charge of "following exactly and carefully the rules to reckon the movements and conjunctions of the stars, sun, and moon. He ordered them to respect the supreme heaven, and to instruct the peoples of the times and seasons suitable for each state." 1 Yao sent the four Mandarins to four spots of the empire and made each of them responsible for the organisation of the works of one season, according to the related solstice or equinox.

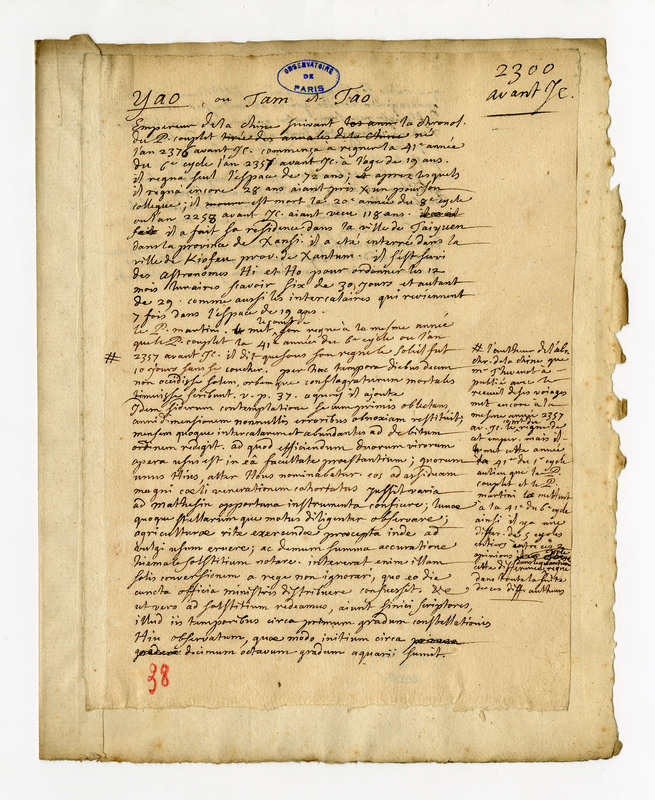

Taking account of this myth, which is supposed to happen in 2300 B.C., and is accompanied by several comments, Father Gaubil strived to identify the places where the astronomers were sent, as well as the constellations they used to calculate solstices and equinoxes. In an independent draft, also collected by Delisle, the translator additionally underlined that this page of the Book of Documents implied the existence of a distinction between a solar year, "which gave the exact places of the sun, moon, and stars, and in which the seasons were marked", and a civil lunar year, which required the addition of a "leap moon" to "bring back the four seasons to the same spots in the year" 2

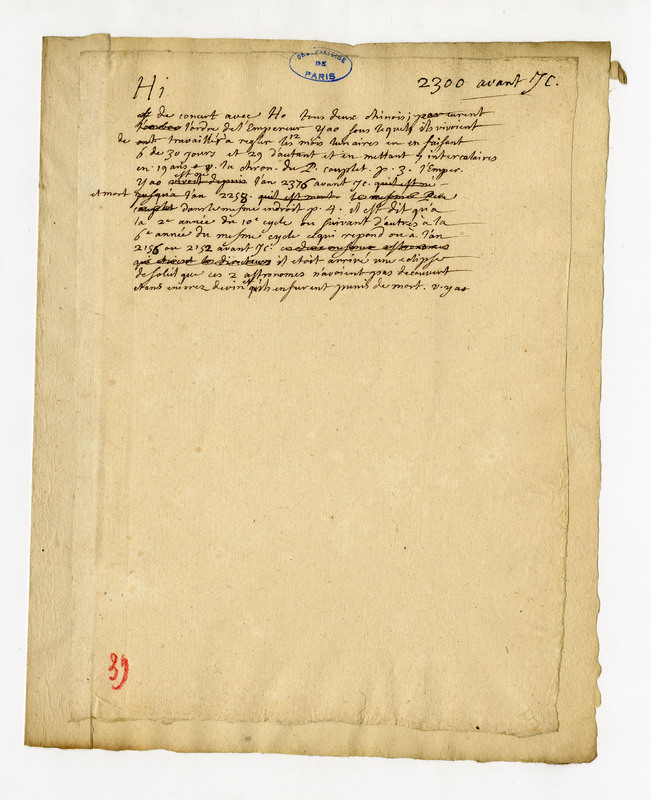

Careful reader of this translation, Delisle also dedicated a few notes to Yao and his astronomers, incidentally grasping some points of the Chinese traditional calendar. He wrote that the Mandarins Hi and Ho "were ordered by Emperor Yao, under whom they lived, to strive to adjust the 12 lunar months, by making out of them 6 of 30 days, and as many of 29 days, and by adding 7 leap months in 19 years." 3

The traditional Chinese calendar indeed belonged to the "lunisolar" calendars : it combined a solar year (nian, 年), defined as "the whole number of days between two consecutive winter solstices" (i.e. 365 or 366 days), and a year of "twelve or thirteen lunar months", represented by the character yue, 月, which refers to the moon. Since a lunar month includes 29 or 30 days, a standard lunar year will only have "353, 354 or 355 days, i.e. 10 to 13 days less than the solar year". 4 To match these two years, it is therefore necessary to add the leap month mentioned by Delisle and Father Gaubil. In 589 B.C., China adopted the cycle known as the "zhang (章) cycle", in which 7 years of 13 lunar months have to be intercalated in 19 solar years. 5]

In addition to the years, diverse other cycles were calculated, in order to give its tempo not only to the celebrations, rites and farm works, but also to the twelve double hours (shi chen, 時辰) a day consists of. A dense network of symbolic correspondences has been built from time immemorial between each of these time-related units and the different components of Chinese cosmology : the twelve animals of the zodiac, the five elements or agents (metal, wood, fire, earth and water), natural phenomena ("insects' awakening", "grains in ear"...), as well as the astrological cycles based on the Nine Palaces (jiu gong, 九宫). The most general frame consists of an ontology of "air" (qi, 氣), where seasons, times of day and night, are regarded as a wide cosmical breathing, also related to the alternation of the yin (陰, night, winter, etc.) and the yang (陽, day, summer, etc.), as well as to the union of the Heaven (tian, 天) and the Earth (di, 地).

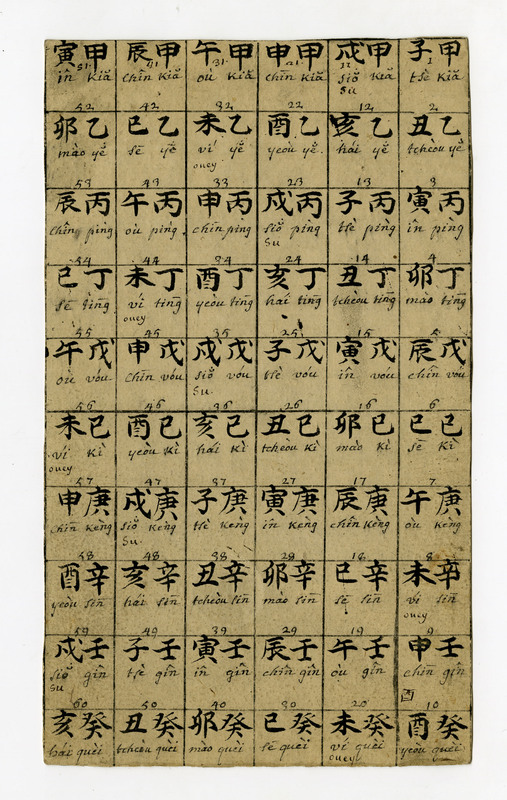

All these rythms peak in the "sexagenary cycle" (ganzhi, 干支), "genuine keystone of the Chinese calendar". 6 Ten "Heavenly Stems" (tiangan, 天干) and twelve "Earthly Branches" (dizhi, 地支) go together to compose sixty "Stem-Branch" pairs :

The sixty "Stem-Branches" resulting from these combinations can correspond to days, months, or years. This counting is obviously of interest to the astronomers, due not only to its extreme ancientness, but also to the continuity of its application. As we learn from Patrick Rocher, researcher at the Institut de Mécanique Céleste et de Calcul des Ephémérides (IMCCE), "as for days and months, the use of the cycle dates back to the 13th century B.C. under the Shāng dynasty (1660 – 1046 B.C.). As for years, the use of the cycle dates back to the Hàn dynasty (202 B.C. – 220). » 7

1 Antoine Gaubil's translation, Delisle collection, portfolio B1/12, paper 2, 2.1, p. 1.

2 Portfolio B2/1, paper 6, 2.

3 Portfolio A7/10, paper 39.

4 Jean-Claude Martzloff, Le calendrier chinois : structure et calculs (104 av. J.-C.-1644), Paris : Honoré Champion, 2009, chap. 2. The quotations come from pages 63 and 69.

5 Patrick Rocher, « Le calendrier traditionnel chinois », site of the Institut de Mécanique Céleste et de Calcul des Ephémérides (IMCCE), Paris Observatory, p. 17. The zhāng (章) symbol here points out the cycle's wholeness.

6 J.-C. Martzloff, Ibid., p. 86.

7 P. Rocher, Ibid., p. 13.